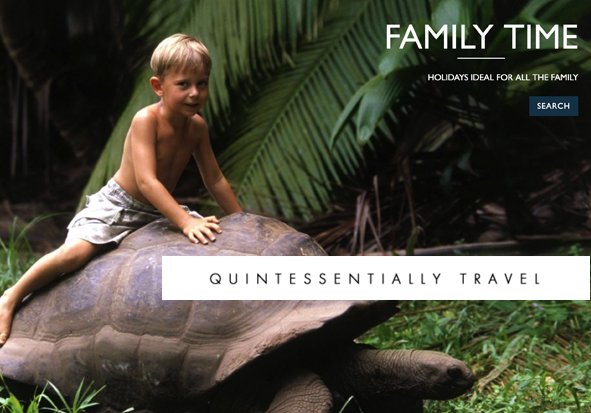

TRAVEL

Surrey’s Premier Lifestyle Magazine

Britain’s last wilderness?

The Knoydart peninsula is the most remote spot in mainland Britain – a haven for flora, fauna and free-range families. Hanna Lindon gets back to nature on a trip to this wilderness paradise.

LOADING

Soldered onto the west coast of Scotland, overlooking the legendary isles of Skye and Rum, is an unassuming little peninsula that might just hide one of Britain’s best-kept travel secrets. This is Knoydart, a place without supermarkets, real roads or any modern trappings of civilisation, only accessible by boat or through a 26-kilometre hike through some of the roughest and most mountainous terrain in the country. It’s the kind of place where Bear Grylls might take his kids on holiday, and for those beguiled by the idea of getting back to nature then it could just be a dream destination.

Knoydart has been on my bucket list ever since I learned that it’s officially home to mainland Britain’s most remote pub. I was intrigued by the stories of beautiful beaches, a spectacular mountain backdrop and seafood fresh off the dock. That’s why, on a misty morning in mid-shoulder season, my husband Guy and I were completing the last leg of a twelve hour journey from our home in Gloucestershire to the peninsula’s main settlement, Inverie.

We’d spent the previous night wild camping in nearby Glen Etive (a place famous for featuring as one of the brooding Scottish backdrops in Skyfall), just to get into the mood. If you’ve never wild camped before then it’s a must-do experience – no caravans, campsite chatter or cars; just you, a campfire and the stars shining above. Wild camping isn’t officially legal in England or Wales, but it is in most areas of Scotland, provided you choose a relatively remote place to pitch up and leave no trace of your presence. Glen Etive is an ideal place to give it a go, as you can park in a secluded spot and camp right next to your vehicle, falling asleep to the chatter of the river that flows down the glen.

We spent the evening recovering from the long drive north with celebratory beers and a warming fire. The next morning it took us a couple of hours to travel the remaining sixty miles to the remote West Highland port of Mallaig, where we hopped on a tiny ferry en-route to Knoydart.

The ferry glided through the calm waters of Loch Nevis, surrounded by a billowing sea of swirling mist. Somewhere up there the sun was doing its best to put in an appearance: arcs of soft light formed faded rainbows beyond the bow of the boat and every now and then there was a flash of forget-me-not blue sky. A smudge of darkness out to our right hinted at the ragged shoreline that twists away from Mallaig towards the wildest corner of Scotland, but otherwise we were sailing serenely along in our own calm white bubble.

“Today’s going to be a cracker when this fog clears,” said the boat’s captain. “You’re unlucky though – we’ve seen dolphins every crossing this week, and I doubt you’ll get a glimpse of them this morning.”

In the cosy front cabin was a poster showing all the marine life that passengers might spot during the journey. Basking sharks, sunfish, porpoises and seals were all pictured, alongside leatherback turtles and more species of dolphin than you could count on one hand. It was a list to rival the world’s most exotic tropical waters and as blue sky spread across the horizon, it seemed difficult to believe that we were still in Britain.

Knoydart has been on my bucket list ever since I learned that it’s officially home to mainland Britain’s most remote pub. I was intrigued by the stories of beautiful beaches, a spectacular mountain backdrop and seafood fresh off the dock. That’s why, on a misty morning in mid-shoulder season, my husband Guy and I were completing the last leg of a twelve hour journey from our home in Gloucestershire to the peninsula’s main settlement, Inverie.

We’d spent the previous night wild camping in nearby Glen Etive (a place famous for featuring as one of the brooding Scottish backdrops in Skyfall), just to get into the mood. If you’ve never wild camped before then it’s a must-do experience – no caravans, campsite chatter or cars; just you, a campfire and the stars shining above. Wild camping isn’t officially legal in England or Wales, but it is in most areas of Scotland, provided you choose a relatively remote place to pitch up and leave no trace of your presence. Glen Etive is an ideal place to give it a go, as you can park in a secluded spot and camp right next to your vehicle, falling asleep to the chatter of the river that flows down the glen.

We spent the evening recovering from the long drive north with celebratory beers and a warming fire. The next morning it took us a couple of hours to travel the remaining sixty miles to the remote West Highland port of Mallaig, where we hopped on a tiny ferry en-route to Knoydart.

The ferry glided through the calm waters of Loch Nevis, surrounded by a billowing sea of swirling mist. Somewhere up there the sun was doing its best to put in an appearance: arcs of soft light formed faded rainbows beyond the bow of the boat and every now and then there was a flash of forget-me-not blue sky. A smudge of darkness out to our right hinted at the ragged shoreline that twists away from Mallaig towards the wildest corner of Scotland, but otherwise we were sailing serenely along in our own calm white bubble.

“Today’s going to be a cracker when this fog clears,” said the boat’s captain. “You’re unlucky though – we’ve seen dolphins every crossing this week, and I doubt you’ll get a glimpse of them this morning.”

In the cosy front cabin was a poster showing all the marine life that passengers might spot during the journey. Basking sharks, sunfish, porpoises and seals were all pictured, alongside leatherback turtles and more species of dolphin than you could count on one hand. It was a list to rival the world’s most exotic tropical waters and as blue sky spread across the horizon, it seemed difficult to believe that we were still in Britain.

I’ll never forget those initial views of Knoydart. Beyond Inverie’s shingle beach, the coastline flowed into a long, sandy cove that gave way in turn to a marching line of rugged, muscular looking mountains. Trails of mist snaked through the trees above the village and wreathed around the string of low whitewashed houses that framed the seafront. Most of what we were seeing was owned by the Knoydart Foundation, a community association that raised £750,000 in 1999 to buy the peninsula from bankrupt private landowners. Today the residents of Inverie and its wild surroundings are mainly incomers fleeing from pressured lives in the southern cities or Knoydart Foundation workers, but that doesn’t stop a close community atmosphere from prevailing.

Inverie itself, with its picturesque cluster of sea-blasted coastal cottages, was even more idyllic than I’d imagined. As our ferry drew into harbour, two children were kayaking in the shallows without an anxious parent in sight. A small family who had travelled with us in the boat got into a battered old Defender left parked and open for them, jaunting off merrily down the bumpy road into the fragrant pine woods that frame the village.

Knoydart always used to be a roughing it destination with an excellent campsite and a bunkhouse, but no real luxury to be had anywhere. Today, that’s all changed. Self-catering eco lodges complete with hot tubs hide among the trees, and there are also some brilliantly cosy B&Bs and guesthouses scattered around the peninsula. If feeling flush, then Knoydart House (Condé Nast Traveller’s ‘Luxury Scottish Winter Retreat’) and the smaller but just as opulent Knoydart Hide are my top picks. An alternative is to make like us and stay in the Old Forge’s Knoydart Snug: a small but superior cottage with faint-making views of the bay and breakfast included.

Feeling peckish after our long journey, Guy and I paused just to drop off our stuff before making a beeline for the pub. Locals were gossiping over drams of golden whisky as we rolled up at The Old Forge’s rustic bar and ordered two seafood platters. The menu claimed that every item on the platter – other than the pots of thick, garlicky dipping sauce – was sourced from within seven miles of Knoydart, so it was the obvious choice. Mind you, I was sorely tempted by the wild venison that had been culled and butchered on the peninsula and was also on sale at the Knoydart Foundation shop next door. It took the arrival of the supersized platter, with its liberal helpings of juicy Loch Nevis langoustine, hand-dived Arisaig scallops, Mallaig-smoked salmon and Loch Nan Uamh rope mussels, to convince us that we’d made the right choice.

Inverie itself, with its picturesque cluster of sea-blasted coastal cottages, was even more idyllic than I’d imagined. As our ferry drew into harbour, two children were kayaking in the shallows without an anxious parent in sight. A small family who had travelled with us in the boat got into a battered old Defender left parked and open for them, jaunting off merrily down the bumpy road into the fragrant pine woods that frame the village.

Knoydart always used to be a roughing it destination with an excellent campsite and a bunkhouse, but no real luxury to be had anywhere. Today, that’s all changed. Self-catering eco lodges complete with hot tubs hide among the trees, and there are also some brilliantly cosy B&Bs and guesthouses scattered around the peninsula. If feeling flush, then Knoydart House (Condé Nast Traveller’s ‘Luxury Scottish Winter Retreat’) and the smaller but just as opulent Knoydart Hide are my top picks. An alternative is to make like us and stay in the Old Forge’s Knoydart Snug: a small but superior cottage with faint-making views of the bay and breakfast included.

Feeling peckish after our long journey, Guy and I paused just to drop off our stuff before making a beeline for the pub. Locals were gossiping over drams of golden whisky as we rolled up at The Old Forge’s rustic bar and ordered two seafood platters. The menu claimed that every item on the platter – other than the pots of thick, garlicky dipping sauce – was sourced from within seven miles of Knoydart, so it was the obvious choice. Mind you, I was sorely tempted by the wild venison that had been culled and butchered on the peninsula and was also on sale at the Knoydart Foundation shop next door. It took the arrival of the supersized platter, with its liberal helpings of juicy Loch Nevis langoustine, hand-dived Arisaig scallops, Mallaig-smoked salmon and Loch Nan Uamh rope mussels, to convince us that we’d made the right choice.

LOADING

“...one of my favourite outings was the Knoydart in a Knutshell trail. This scenic two-hour hike winds through the pretty pine woods above Inverie before descending to meet the mouth of Inverie River and meandering back again along the beach.”

Hanna LindonThe best way to work off a big meal in Knoydart is to lace up the walking boots and go for a tramp. During our time on the peninsula we did plenty of hiking, even managing to tackle one of the three ‘Munros’ (that’s Scottish mountains over 3,000 feet high for the uninitiated), but one of my favourite outings was the Knoydart in a Knutshell trail. This scenic two-hour hike winds through the pretty pine woods above Inverie before descending to meet the mouth of Inverie River and meandering back again along the beach. Children, big and small, will love searching for shells on this huge expanse of sand, and discovering the odd wooden sculpture that emerges at low tide.

The joys of Knoydart are mainly walking, relaxing, paddling and soaking up nature in its unadulterated state, but the peninsula isn’t short of great places to eat either. We enjoyed some scrumptious fair trade teas at the Knoydart Pottery & Tearoom as well as dinner at the Dining Room at Doune. Despite being located a six-mile four wheel drive journey from Inverie followed by a fifteen minute walk down a rough path, this tiny eatery has built up a well-deserved reputation for incredible ‘slow’ food based around locally sourced products.

We left Knoydart after three days feeling refreshed and revived, and this time there was no sea mist to disguise the knockout views towards the Western Isles as the ferry carried us speedily back across Loch Nevis to Mallaig. We broke our journey in the beautiful valley of Glen Coe this time, stumbling across a lone bagpiper on our walk around this legendary region and finishing up with yet another al fresco, fireside meal in the most secluded spot we could find.

“A toast?” suggested Guy, holding up his beer as the sinking sun turned the mountains pink.

“Why not?” I said. “Here’s to the call of the wild.”

All images courtesy Hanna Lindon

Go explore...

Getting there: Seabridge Knoydart (www.knoydartferry.com) operates a ferry service from Mallaig to Inverie, and a return will set you back £20. For day trips you can park for free at Mallaig’s harbour, which is a scenic one and a half hour drive from Glencoe.Getting around: Visitors are not permitted to bring vehicles on to the peninsula, so walking is the preferred mode of transport. Land Rover hire is, however, available from some guesthouses and with Seabridge.

When to go: Avoid the winter months, when the ferry is unreliable and the weather arctic. June, July and August are also made difficult by western Scotland’s voracious midge population. Spring and autumn are both perfect times to visit Knoydart.

Where to stay: Knoydart House (www.knoydarthouse.co.uk) or Knoydart Hide (www.knoydarthide.co.uk) for luxury, or Knoydart Snug (www.theoldforge.co.uk/knoydart-snug.html) for more modest budgets.

Where to eat: The Old Forge (www.theoldforge.co.uk) and The Dining Room at Doune (www.doune-knoydart.co.uk) are both top-class places to eat. The award-winning Lochleven Seafood Café (www.lochlevenseafoodcafe.co.uk) near Glencoe is another top choice.

Top attractions: Accompany a ranger on a wildlife-tracking expedition with Wild Knoydart Experience (www.knoydart-foundation.com), take a Land Rover tour (www.knoydart-foundation.com) or join the scheduled walks that leave Inverie every Wednesday at 11.30am.

Guidebooks: Lonely Planet (www.lonelyplanet.com) and Rough Guides (www.roughguides.com) both publish Scotland guidebooks that cover Knoydart.

Find out more: The Knoydart Foundation (www.knoydart-foundation.com) is an invaluable source of information, as is Visit Knoydart (www.visitknoydart.co.uk).